On Tools and Concepts and Practical Capabilities

Make or Buy… or Pretend and Drop Behind

When you want to acquire a new skill or learn something new, you turn to any of several sources, from the internet (Google, YouTube, blogs, etc.) to books to training courses or even academic programs. It all depends on how much you need to learn, how deep you want to go, and what you want to do with it. For the interest of this article, I will limit to wanting to acquire enough knowledge for practical application at work. Let us call this capability development, whereby you want to develop yourself or your team, often through training, to be capable of usefully applying the skill, as opposed to outsourcing it to a consultancy or hiring new headcount who already acquired that skill elsewhere and is ready to apply it for your benefit.

At that point, you are faced with the variation in styles and approaches to training. Over the years I have been coming across this recurring theme: pitting tool-focused and methodology-focused training against an approach based on concepts alone as two mutually exclusive approaches, in the name of being principle-centered and of advocating critical thinking, and to thwart the threat of limiting minds to prescriptive approaches that stifle imagination and creativity and make the novice practitioner a prisoner to the method rather than an astute applier of it.

This theme has underpinning drivers: For some the quest for agility makes them view methodology as synonymous to rigidity in principle. For others, it is a belief that methods are technicalities beneath the leadership requisite in their position, whereby they see using tools and respecting standards or methodologies as something to be delegated to low-ranking (and often under-paid) subordinates or outsourced to the handyman. A third driver for some is their deep suspicion that following a method is inherently counter-creative and that any hint of discipline or standard is poisonous to innovation. Often you see a combination of two or all these drivers entrenched in the frame of reference of people in decision-making positions. And the frame of reference of the person in authority is invariably parroted by the troops, regardless if the authority in question is old-fashioned raw power or if the power is garnished by politically correct leadership.

This came across in multiple examples. To name few, of various types, look at this book, The Blockchain Revolution, by Tapscott & Tapscott: the “revolution” in question being technological in origin, the book does not explain but too little of the underlying technology, leaving the avid coder disinterested. The sentiment is best captured in this recent comment by Andrew Mathews, a project management professional who commented on an hour long webinar on Disciplined Agile by the Project Management Institute with these words of criticism: "I am interested in learning what specific enablers and tools are available within the Disciplined Agile toolkit, now. This is a good presentation for giving you an overview of what DA is about. However, I didn't take away anything that I can use immediately." You also see this phenomenon in the avalanche of thought leadership literature in the form of white papers – and lately in the form of webinars and their slide decks – bubbling up out of management consultancy houses: invariably studded with fancy charts or rendered in pure info-graphical format but rarely walking you through the technique as to how they got to their conclusions, since doing so is only useful by means of validating their product to the odd skeptic purchasing executive.

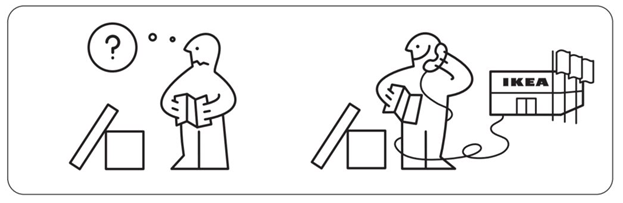

Regardless of what any individual may choose for themselves, no work can be done without the right tools or at least be done efficiently. To dismiss a tool set is to compromise on speed or on accuracy. If you are not using the right tools, you will be falling behind. If you give your time to conferences and webinars and neglect proper hand-on training, you will become better at conversing with the expert consultants you meet at these venues and exchange business cards and connect over LinkedIn and engage in discussions, but will not develop your own capabilities and, when faced with real challenges in your workplace, you will have to choose between staying behind or checking the budget and fishing for those business cards.

Illustration source: IKEA

Click below to learn how

NEXCELLENCE

can help you with this challenge

Why is this an issue? When I was a kid in school, one old English language teacher planted this idea in my head: building vocabulary is equipping the mind with building blocks to construct ideas and express oneself. Going out in the world with poor vocabulary, he said, is like going to war with a limited arsenal. Any analyst new in their work will quickly sense an indirect correlation between time spent on analytical work and the repertoire of Excel functions that they master. The same goes for the repertoire of soft skills necessary for effective leadership. To choose a path devoid from technical skill acquisition is a path to becoming a dinosaur unless one manages to acquire the impression of being abreast of advancement by means of immersing in conferences and webinars replete with the buzzwords of the quarter (blockchain, IoT, digital transformation, etc.) whereby matters are “explained” in short and shallow presentations leaving attendees confident and satisfied and incapable of tackling technical challenges lest for hiring the handyman (read: the consultant) who can.

Thanks to these mindsets, the challenge of acquiring technical skills becomes dual: For one, you have the concern of becoming perceived as an eternal tech head and becoming cast into the technical career path which often denies you the glamorous and better-paid ‘leadership’ path. For two, as the years progress with more meetings and people leadership issues consuming your time, you start sensing a widening gap between what you know and can do and what younger handymen know and can do. You start consuming this Aspirin branded as “Your analyst can do it for you” or “These technical skills are important that’s why we hire consultants / junior staff who can do them”, while your job becomes more about leading others. These lines of lyrics from a 1965 song come to mind: “Même si lassé d'être chanteur, j'y sois devenu maître chanteur, et qu'ce soit les autres qui chantent” (J. Brel) which translate as “even if, tired of being a singer, I were to become a chief singer, and that it would be the others who sing” - the lyrics go on to assert that no matter what, the old times of early beginnings are never forgotten). At this point one must choose: abandon the quest of keeping up or learning technical skills altogether? Letting them become a hobby for tinkering around on weekends? And, most importantly, which skills to pick and which skills to leave for the others?