Try this: Ask a random colleague or business associate the following question: In your opinion, what percentage of business professionals use spreadsheets in their work? The answer will invariably be one of three types: Either a qualitative one (e.g. “a lot” or “everyone I know does” or a variation thereof) or a quantitative one, venturing a number or a range (e.g. “I think at least 90%”) – that may be a guess rooted in unsubstantiated confidence or a well-informed referenceable figure – or, if your colleague is indifferent or enjoys scientific humility and has no particular reference in mind, you may get the “I don’t know” answer.

Here's the thing: What kind of answer – you the reader – thought of when you read the question? And did you notice; the percentage is out there in the real world and should not be a matter of anyone’s opinion? After all, the actual use of software by others is not consequent to your preference.

Now consider the following questions, and imagine them in the context of a meeting or a panel discussion:

Do younger professionals prefer Google Sheets and are abandoning Microsoft Excel?

Are Mac users less likely to use Microsoft Excel compared to those on Windows?

Give these questions a thought. Throw them around colleagues over a coffee break and get a conversation going. Take note of how people engage in conversation, particularly the kind of affirmative sentences they may speak. You may hear things like “Excel is dying”, “the young generation prefers web-based applications”, or even “Mac users don’t use spreadsheets”. Reading those examples, you may be mentally nodding in agreement or eager to comment in disagreement.

Granted, these topics are not popular in 2025 when most talks and discussions around technical issues in business have been focused on the novelty of AI away from the entry-level mundane tools that spreadsheets are. Nonetheless, these tools – operating systems and spreadsheets – were selected for a quick survey specifically because they are ubiquitous, well established, and have been in continual use for decades since the early days of personal computers.

As you probably guessed by now, this article is not about operating systems and spreadsheet software. The survey thereon is a tool to demonstrate how reality may differ from perceptions like those statements in quotation marks above. Let’s take them and get skeptical: Is Excel a dominant spreadsheet software? Are younger people less likely to prefer it over Google Sheets? Do MacOS users work on Excel? Are they less likely to use Excel?

I ask you to notice how your brain is already working out the answers to these questions. If you ask them to someone else and they answer with anything other than “I don’t know”, challenge them: Ask them “how can you tell?” and see if they justify with confidence. So far, it’s about thoughts in brains. Opinions and/or memory and/or seemingly logical thinking that borrows from the baggage of perceptions about generations and their preferences and so on. But is that the same as reality out there? What do we see when we ask a hundred different people? And what can we learn about our own thinking process from this exercise?

That’s what this survey and article try to shed light on. Three simple questions in an anonymous Google Form disseminated over social media (LinkedIn and Facebook) and messaging groups (WhatsApp, Signal, Line) across several countries including but not limited to Thailand, UAE, Australia, Egypt, India, Canada, and Switzerland and across a diverse range of professionals and students as young as 15 and as old as 74 (based on the youngest and oldest who shared completing it, not withstanding anyone else who has not shared and might be older or younger).

The survey asked three questions with pre-defined options to choose from:

1. What year were you born?

2. Which operating system runs the device you consider as the main device for your work or study?

3. Which spreadsheet software do you prefer to use? (pick the one you prefer even if different from the one you may be required to use)

The survey was terminated few days after collecting 104 responses.

How many answered “I don’t use spreadsheets at all” in response to third question? Are you tempted to imagine these must all be either very old or very young? Well, only three (2.9%) did. They were one Baby Boomer (born 1946-1964), one Gen-X (1965-1980), and one millennial (1981-1996). The Baby Boomer was on Windows and the other two on MacOS. Could you conclude anything about age and use of spreadsheets? Of course not. Are you tempted to conclude anyway? Of course, yes. At least I was before seeing the tiny count of just three.

For what it’s worth, I asked Google “What percentage of business professionals use spreadsheets in their work?” on the afternoon of November 25th, 2025: The AI Overview kicked in and said approximately 80% of businesses rely on spreadsheets. Specifically, Google’s AI said 80% of businesses rely on Microsoft Excel. Keep that in mind. Also note this is Google that offers an alternative to Excel, Google Sheets. Now, did you notice that I asked about business professionals and the AI answered in terms of businesses and not in terms of people? I asked the exact same question to another AI, Claude (Sonnet 4.5): It said “around 54% of businesses globally use Excel specifically” – again answering not on people but on businesses but also more interestingly giving the impression Excel is way less popular (54%) than what Google’s AI said (80%). In our primary market research here, over 97% of the 104 respondents use spreadsheets – Excel or otherwise.

Now let’s get to the meat of this matter: Let’s dive into the 101 who do use spreadsheets and, now that we had AI singing the glory of Microsoft Excel, let’s see if our small sample is closer to Google’s opinion (80%) or Claude’s opinion (54%). The attribution of the term “opinion” to AI is deliberate here on grounds of lacking clarity exactly how AI works among the public and the intent to caution against taking whatever AI says as truth. Remember the days in the late 1990s when we had to be reminded not to believe anything the internet says?

To the question “Which spreadsheet software do you prefer to use?”, 75% preferred Excel, 24% preferred Google Sheets, and one single respondent – Gen-X on MacOS – indicated they prefer LibreOffice Calc (no that’s not me; I’m a GenX on Linux and Windows using both Microsoft Excel on Windows and LibreOffice Calc on Linux, the former being my preferred spreadsheet software although the latter is a very close and perfectly free and open source contender)

Now, might we imagine that being on Windows and using Excel go hand in hand and that we are more likely to find Google Sheets users sporting MacBooks? Could we get curious or have a hunch that older folks are probably entrenched in Excel whereas the younger generations are more likely Google Sheets users? Opinions and guesswork… What does the data tell us?

Before properly listening to our 101 respondents to find the answers, remember this is just an example: You could replace “Excel” and “Google Sheets” with the product you are selling and its competitors. You could replace “Windows” and “MacOS” with the service you are advertising. In your business you make decisions about where to advertise, what marketing channel to use, and what kind of clients to aim for. Decisions that require budgets and put a dent on your profitability and/or take up your time. Are your decisions based on hunches? Based on the experience of the marketing agency that is billing you? Or are you confident with a high degree of probability that your decisions are correct? Face it: Who are you listening to? Is it your pride posing as experience and hiding behind confidence following a good dose of positivity from your inspirational guru and lecturing you about gut feeling and courage? Is it the claim from your marketing agency? Or is it the voice of your customers and the data from your business?

Here is how to listen to the voice of your customers, using this simple survey and its possible interpretations as example.

There are three variables in the survey: Age group, operating system, and spreadsheet software or lack thereof. Moving forward the three who do not use spreadsheets at all are removed (in statistical jargon we say “brushed”) and the rest of the analysis focuses on the 101 who use spreadsheets.

The age groups could have been one of six based on options given to respondents, but none were born before 1946 or after 2012, so the dataset has four age groups: Baby Boomers (7% of respondents), Generation X (57%), Millennials (17%), and Gen-Z (19%). For the sake of simplicity, the older two and the younger two are grouped, so anyone born before 1981 is labelled “older” (64%) and the rest labelled “younger” (36%).

The operating systems could be Windows (74% of respondents), MacOS (21%), Linux (3%), or “Something else” (2%) – left general to accommodate for users of tablets and smartphones (yes, there are people who don’t use laptops or desktops. They roam among us). For the sake of simplicity and given the small numbers outside Windows and MacOS, these are grouped in two dichotomous groups: Windows (74%) versus Non-Windows (26%) and MacOS (21%) versus Non-MacOS (79%). As noted above, spreadsheet software could be Microsoft Excel (75%), Google Sheets (24%), or LibreOffice Calc (1%). A caveat here is that Microsoft Excel cannot be installed on Linux whereas Google Sheets and LibreOffice Calc can be used on any operating system.

So, what can the dataset tell us about the associations or lack thereof among any two of these three variables? Let’s interrogate the data using statistical hypothesis testing. In simple terms, statistics is this branch of mathematics that can calculate the odds of matters being totally random using calculations we call “hypothesis tests”. Keep in mind it’s about probabilities not about certainties. The term “confidence” is aptly borrowed by the statistical jargon to carry this crucial nuance. This implies when you look at what statistics say, you will invariably need to decide based on odds, knowing your decision could be an error but taking the chance as you see the odds numerically calculated and you are willing to judge them as low enough. Keep in mind this difference between statistics and the determinism you see in the formulae of classical physics describing natural laws like the gravity of Earth or atmospheric pressure and so on.

Interrogation Question 1: Data, tell us if the use of Windows versus other operating systems is associated with being older or younger, and tell us if it’s reasonable to believe older people are more likely to be on Windows.

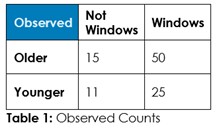

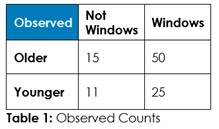

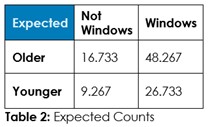

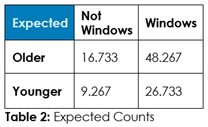

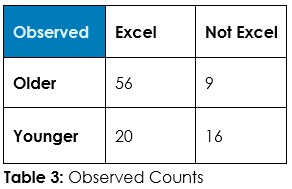

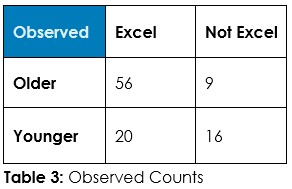

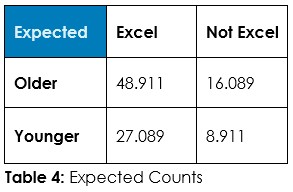

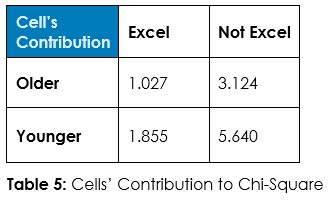

Answer 1: Tabulate the observed counts in Table 1 and run Chi-Square statistical test to calculate expected counts if randomness dominates (Table 2) and calculate the odds of randomness instead of an association so we can decide about this hypothesized association – if we should admit random chance or if we should decide an association exists.