Performance Management Practices & Systems

Insights from a Survey of Performance Management Professionals

This article includes insights and reflections on practices in performance management based on the responses of professionals across sectors, industries, and geographies to a primary research survey conducted by NEXCELLENCE consultancy between August 2020 and January 2021. The survey responses are hereby analyzed and reported along with thoughts and further hypotheses for future research.

This survey enabled testing some interesting assumptions, corrected preconceived notions, and revealed gaps and facts on practices in performance management that may not be apparent to the individual professional or single organization. The effort is intended to offer a wider perspective to strategy execution professionals and performance managers as they continuously seek to upgrade the added value of the function.

Background

As organizations are striving to achieve the mission they were built for, strategizing kicks in with focus trade-offs, investment decisions, structuring decisions, and communicated directions, all aiming to serve the mission. As strategies are cascaded and implemented, performance goals and targets are set for the organization, its sub-divisions, and for the individuals at all levels, ideally in full alignment and optimized resource allocation. What follows is action planning and execution to achieve the targets. Then comes the next tenet of management: monitoring and controlling. In the words of Winston Churchill, “However beautiful the strategy, you should occasionally look at the results.” How best this can be achieved varies in detail from one organization to another but at the end, clarity on performance is needed. To that extent, performance management is necessary regardless as to whether a performance management function is defined and resourced, where it sits in the organization, whether its primary focus is organizational or individual performance or both, and what tools are used to track, report, and act on results.

Click below to learn how

NEXCELLENCE

can help you with this challenge

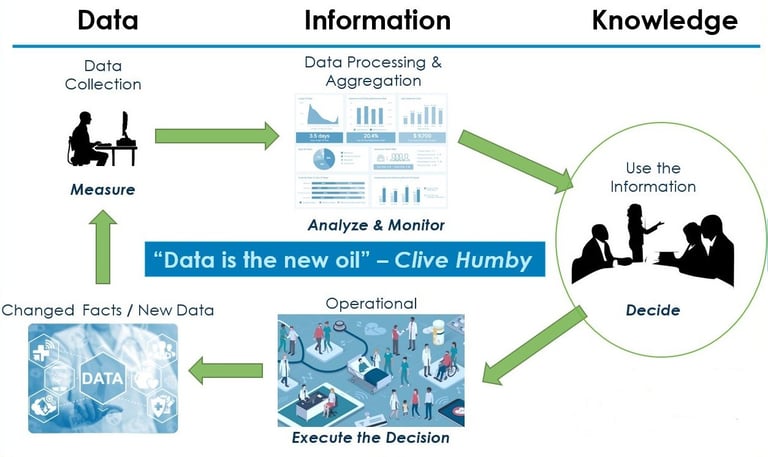

Figure 1: Data-driven decision-making follows a cycle & feedback loop for continuous adjustment

Any professional who has been around realizes that the concept of performance management and the tools it utilizes vary widely from one organization to another and evolves over time in any given organization. Some are focused on the individual human resource and conduct performance management to inform staffing decisions and compensation & benefits decisions. Other organizations believe performance management should be geared to understanding how the organization is doing vis-à-vis its strategic objectives and pertinent time-scoped targets, with performance management sitting within a strategic planning / execution office and oversees organizational-level key performance indicators.

And some organizations understand that both are necessary and need to be in full alignment rather than being managed in a dissociated manner following separate processes with different systems.

To understand the landscape of these variations in practices and tools among performance management professionals, NEXCELLENCE launched a primary research survey in August 2020. The survey was designed to explore potential associations between segmentation factors on one hand (such as organization size, multinational or not, sector being government or private for-profit etc., and geographic region) and practices on the other hand (if performance management is assigned, if it is under Human Resources or has its own function, if the organization uses a performance management system or not, and if they have switched systems or not). The survey also explored perceptions of utility for attributes and features commonly offered by various performance management software solutions as well as familiarity and perceptions of selected leading performance management software.

Methods

A quantitative structured questionnaire was designed and hosted online over Google Forms. Collection of respondent e-mails was disabled in line with the promise of anonymity. Respondents were given the option to write down their e-mail if they wish to receive further information. The fielding of the survey started in late August 2020 with the survey link remaining open until early February 2021. LinkedIn was used to solicit responses with messages targeting performance management professionals globally and regardless of industry (random sampling). The LinkedIn messages were issued from the personal LinkedIn account of the author. The questionnaire avoided Likert scales to prevent acquiescence response bias and to simplify the analysis. Aggregation and graphing were done using MS Excel and statistical hypothesis testing was done with SigmaXL®. Unless otherwise mentioned, the chi-square test was used for hypothesis testing of possible associations between nominal variables (counts by category). Alpha level of 0.05 was used as the threshold for statistical significance.

Results – Respondents and Organizations in the Sample

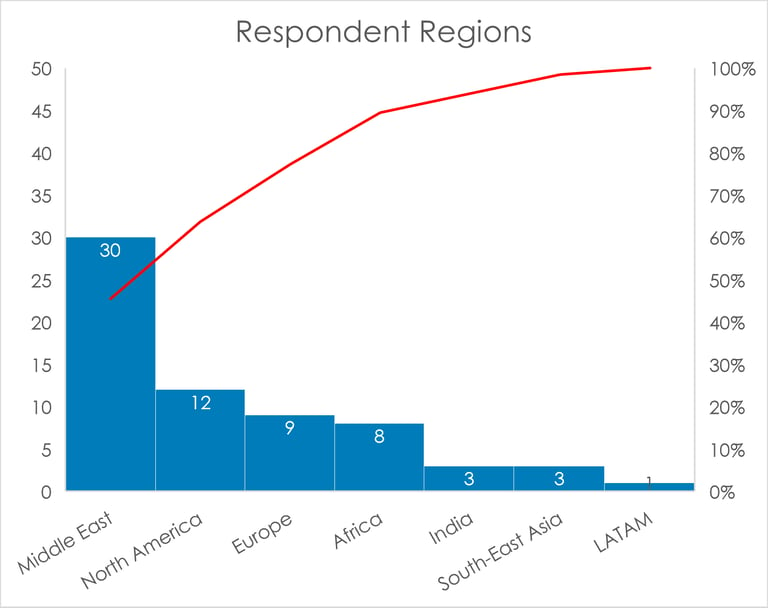

66 respondents from 18 countries filled and submitted the survey. Most respondents (45%) were in the Middle East, 18% were in the US and Canada, 14% in Europe, 12% in Africa, 10% in South-East Asia and India, and 2% in Central/South America.

Figure 2: Geographic distribution of respondents

Respondent countries are, in alphabetical order, Algeria, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Jordan, Kenya, Kuwait, Lebanon, Mexico, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, and the United States.

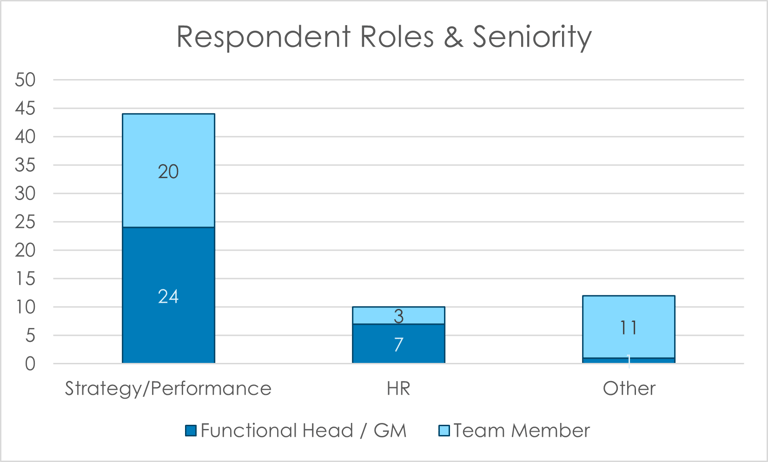

In terms of roles, 67% worked in strategy / performance management, 15% in human resources, and the rest in various other functions including general management. Almost half (48%) identified themselves as department heads or in general management positions.

Most organizations (71%) were for-profit, 21% were governmental or semi-governmental, 5% were academic, and 3% were not-for-profit, NGO, or charity organizations. 62% of respondents reported working in multinational organizations.

Figure 3: Respondent count by function and seniority

More than half (53%) of the organizations had more than 1,000 employees, 6% were between 500 and 1,000, almost one quarter were between 50 and 500, and the remaining were small with less than 50 employees. Organizations are categorized as ‘large’ if they have over 500 employees.

Results – Performance Management Practices and Systems Adoption

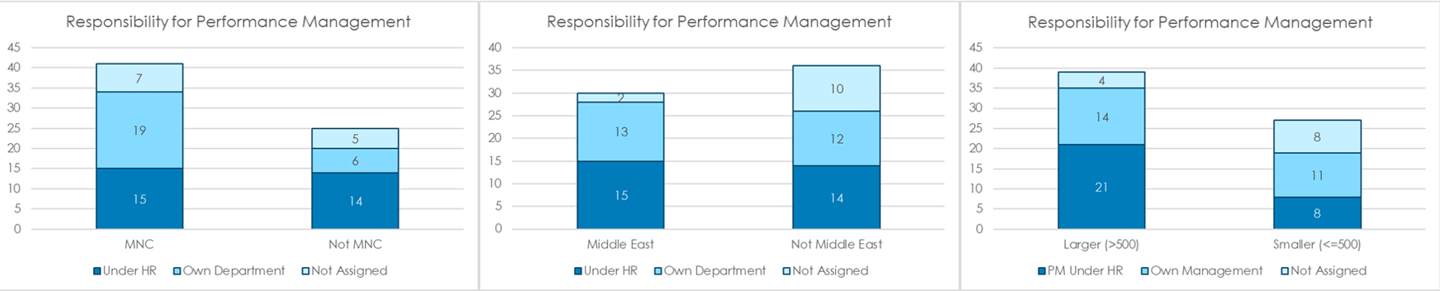

The responsibility for performance management was reported to fall under HR in 44% of organizations, under its own managerial function in 38% of organizations, and as an unassigned function in 18% of organizations.

Whether performance management is under HR was not significantly associated with the organization being multinational, the organization being in the Middle East or outside it or with the organization having over or under 500 employees.

Figure 4: Distribution of Performance Management Responsibility by Organization Types

Interestingly, 90% of HR respondents mentioned Performance Management is under HR whereas only 52% of Strategy/Performance Management respondents mentioned their function manages performance (with 30% noting it is managed not by themselves but by HR). The respondent being an HR professional is significantly associated (p-value: 0.002) with the likelihood that performance management is under HR. This may sound obvious if it were not for the high proportion of strategy/performance managers who reported that their function does not manage performance and sheds doubts on the consistency of defining the same function across different organizations.

It is interesting to see this together with answers to the question “why do you need a successful strategy implementation?” where 41% of respondents cited planning and management considerations and only 24% noted the importance of securing implementation of the strategy (also noteworthy is that 22% of respondents left this question unanswered and only 3% cited reasons associated with compensation and benefits). Some even mentioned there is “no need” to have a successful strategy implementation or noted this as not applicable. One respondent mentioned the reason is to “maintain funding” and another wrote “to justify the relevance of our department”. Nonetheless, others cited the achievement of corporate goals, the monitoring of strategy implementation and follow-through on strategic plans, and to adjust course over time. Not surprisingly then, a massive 38% of respondents mentioned their organizations do not use a dedicated system for performance management – a gap that was equally distributed between multinational and local organizations and prevalent both in the Middle East and elsewhere but, expectantly, more prevalent in smaller organizations. Alarmingly, 20% of respondents noted their organizations never had a performance management system and are not planning to use one. Of these, 23% are large (>500 employees) and 38% are medium (>50 employees). Further, it is not likely that those 20% respondents who mentioned no intention to adopt a performance management system to be speculating from a position of no-influence since all of them noted they either control the budget or make recommendations for system purchase. Also noteworthy is that none of them work in Human Resources with almost all working in strategy / performance management functions.

When probed as to why successful strategy implementation is important personally, responses varied widely with no single dominant theme. Some responses were expected (e.g., “To have a tool to measure success” or “to push the company to higher growth and have a coordinated strategy across all departments”), others were candid (e.g., “to justify my work and salary”), and many revolved around typical monitoring and controlling aspects (e.g., “to manage staff more efficiently and address issues immediately”).

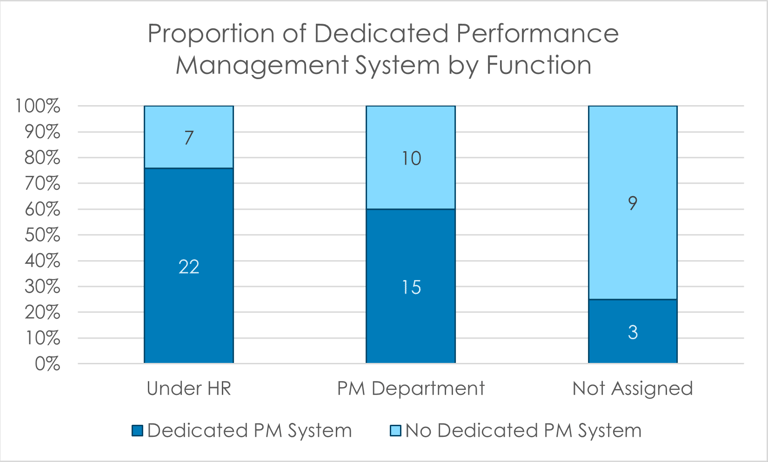

Aside from whether there is intention to adopt a performance management system in the future, almost 40% of respondents reported no dedicated performance management system at present. Interestingly, the 60% who reported having a dedicated system included 25% of the organizations where the performance management function is not assigned to any department (see Figure 5 below). Although a higher proportion of organizations where HR manages performance has a dedicated system compared to organizations where performance management is under its own department, the association is not statistically significant.

Figure 5: Proportion of dedicated performance management system by function

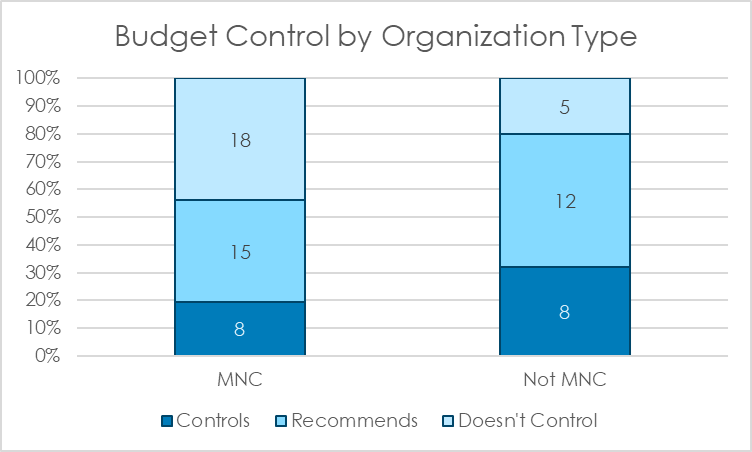

The distribution of controlling or influencing decisions concerning performance management systems is depicted in Figure 6 below: most respondents (65%) either control the budget or make recommendation concerning performance management system choice. There was no significant association with multinational or local status although there was no question in the survey to probe if respondents in multinational organizations are in headquarter positions or in local subsidiaries.

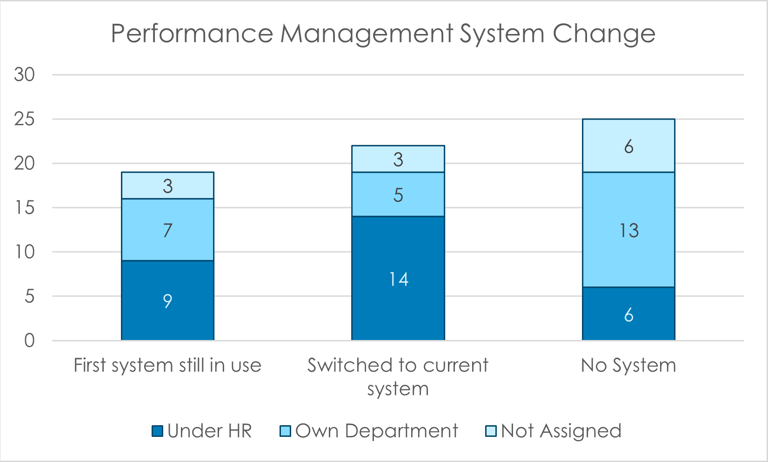

When asked if the organization switched systems for performance management, over half (54%) of those who use a system reported switching systems, depicting a material proportion of organizations who had reason to abandon their performance management system and opt for another.

Figure 6: Respondent level of control by organization type

There was, however, no significant association between switching systems and whether performance management is managed by HR or not, and no significant difference between the Middle East and elsewhere. Alarmingly though, almost 29% of organizations are reported to use no system for performance management. This proportion should be taken directionally, since 13 respondents reported no system is used where performance management has its own department, whereas an earlier survey question had only 10 reporting the same for the same subgroup, underlining the general caveat of survey-collected data.

Figure 7: Counts of organizations by system switching status

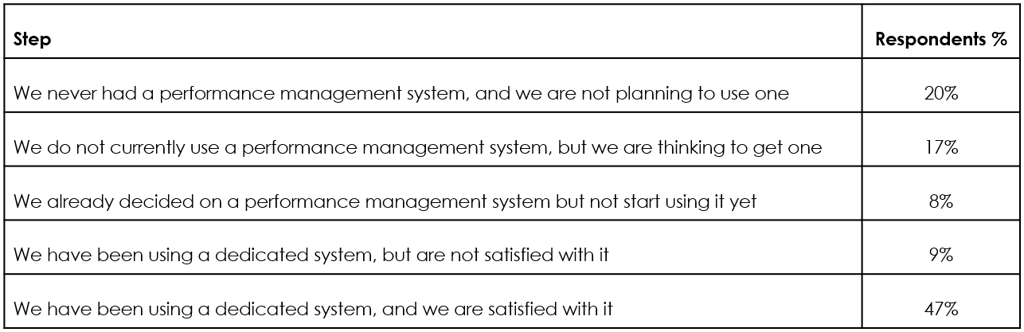

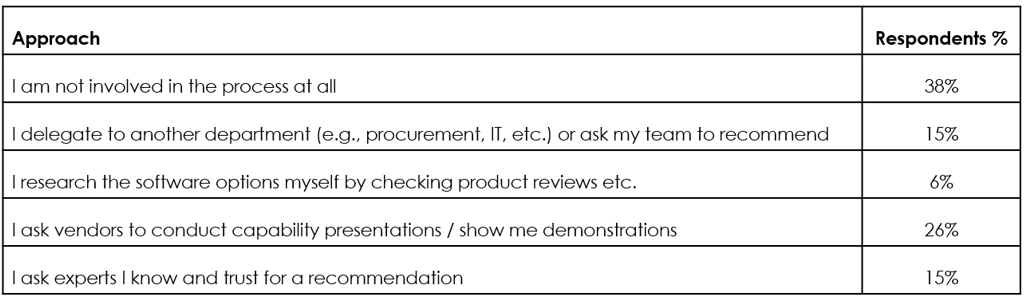

Respondents reported their organizations being on different steps in the continuum to adopt a performance management system, with 47% reporting using a system and being satisfied with it and only 9% reporting dissatisfaction with their current system. A bit under half reported not using a system at present, most of them reporting not having plans to use a system (see Table 1).

Table 1: Performance management system adoption continuum

As expected, only a small percentage (8%) indicated a decision was already made regarding a performance management system, but implementation is not yet in place.

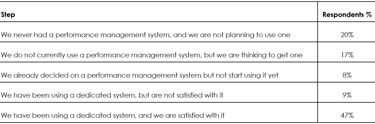

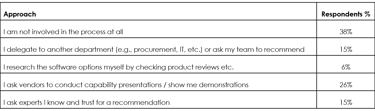

Of the 62% who reported being involved in one way or another in the process of deciding on or procuring a performance management system, the majority reported relying on vendor capability presentations or software demonstrations, almost double those who refer to expert opinion and recommendation. Only 6% reported researching product reviews themselves.

Table 2: Approaches to selecting a performance management system

Not all survey respondents are involved in the process of searching for and deciding on a performance management system: only 30% of those in multinational organizations and 92% outside multi-nationals conduct the search themselves. In fact, one respondent commented as follows: “this feels a bit moot - in multinational companies these systems are pre-selected […]. Specialized offerings for one functionality are rarely considered.”

Interestingly, the process seems to be time-consuming with 53% of respondents investing over a year in the process and only 16% reporting one month of less. While the survey did not probe for reasons behind the delay, one could speculate it is related to the process of searching and selecting, especially that straight Google search accounted for most search methods (61%) with tapping into professional groups for user experience or expert recommendation as a distant second (11%). Free trials of software accounted for only 8% and reference to application directories and review sites (such as Gartner, G2, Capterra, etc.) accounted for only 6%. Alarmingly, establishing business requirements and looking for alternatives to address them was selected by only 1%.

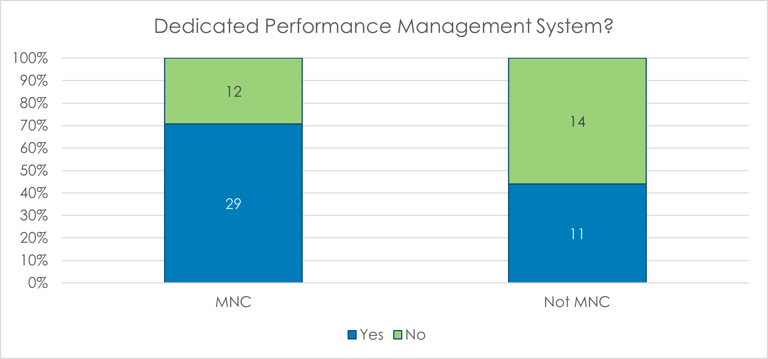

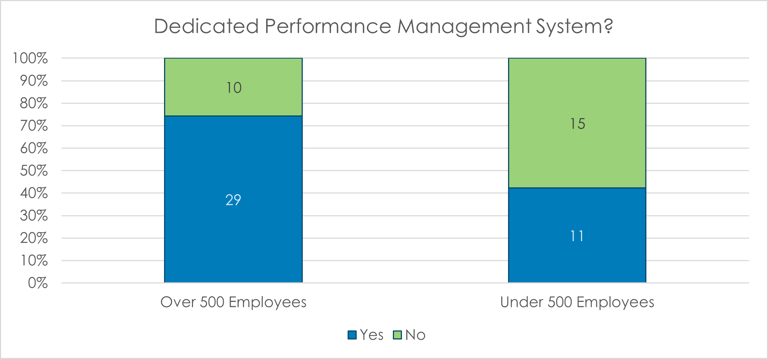

When asked if performance management processes are hosted/conducted using a dedicated system, a substantial proportion (39%) of respondents answered no. This was significantly associated (p-value 0.031) with the organization not being a multinational company. The picture is even more pronounced for smaller companies with a significant association (p-value 0.009) between smaller size (under 500 employees) and not having a dedicated system for performance management.

Figure 8: Proportion of dedicated system by organization type

Figure 9: Proportion of dedicated system by organization size

Results – Performance Management Systems: Experience and Perceptions

Respondents who reported using a performance management system mentioned a wide variety of systems. Of those who specified a system, most (38%) reported using bespoke in-house systems or simply using Microsoft Excel sheets, followed by Oracle-based systems (11%). Fifteen other systems were mentioned including but not limited to SAP / Workday, IBM Cognos, and Corporater. Interestingly, 3% mentioned using multiple systems, perhaps reflecting separate verticals for managing various aspects of performance.

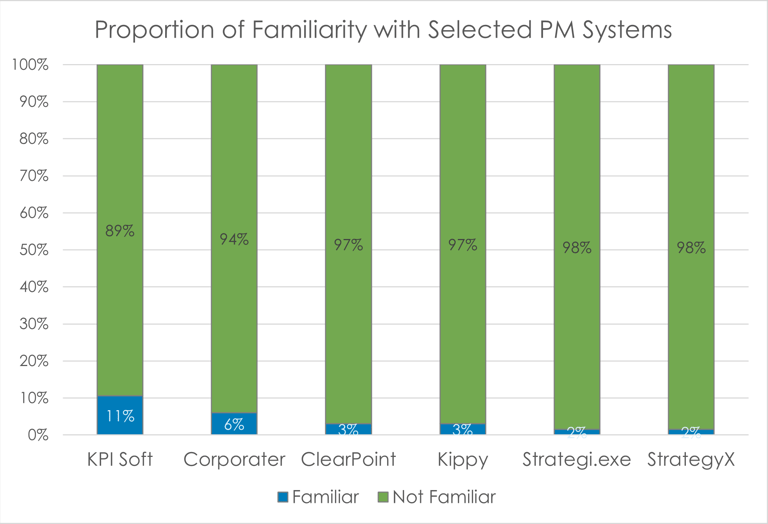

When probed to mention the top-of-mind performance management system, an overwhelming 86% did not specify any system. Oracle and Corporater received a meager 3% each, with five other systems receiving 2% each. This general unawareness of available performance management systems was confirmed again when respondents were probed on their level of familiarity with six selected systems, which scored between 2% and 11% awareness (see Figure 10).

Figure 10: Proportion of familiarity with selected performance management systems

Click below to learn how

NEXCELLENCE

can help you with this challenge

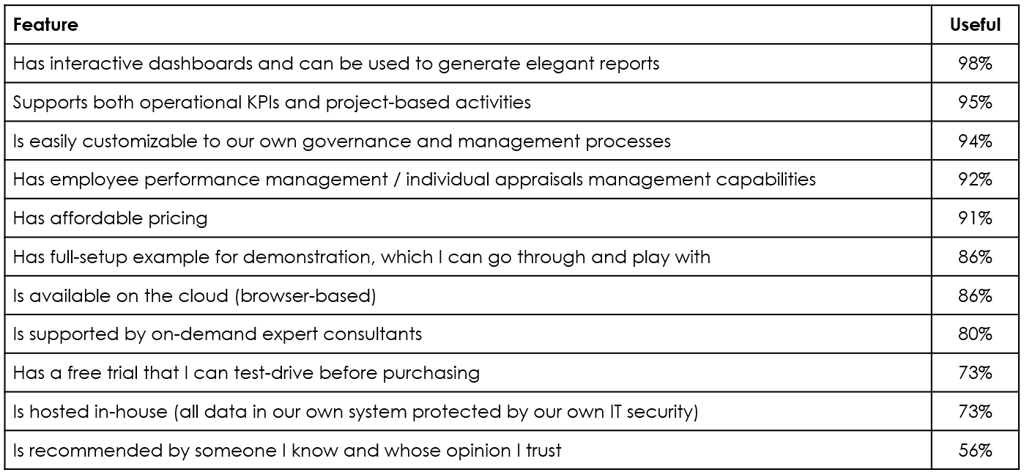

Aside from familiarity with various systems, respondents were asked to judge various common system features as useful or not. Table 3 lists the features in descending order of usefulness (depicted as percentage of respondents who judged the feature useful).

Table 3: Perception of usefulness for common system features

While most features were deemed useful by more than 75% of respondents, it was surprising to see in-house data hosting as one of the bottom three features, which goes to the advantage of cloud-based systems. The recommendation by community of practice leaders ranked lowest with about half respondents deeming it not useful. Almost one in ten deemed it not useful to have a system that hosts employee performance management.

This could indicate a possible gap in alignment between corporate performance and the cascading to employee performance management. Beyond the general familiarity question, the survey probed respondents to specify the degree to which they are aware of or are using six performance management systems and whether they are satisfied with them. Results are summarized in Table 4 below.

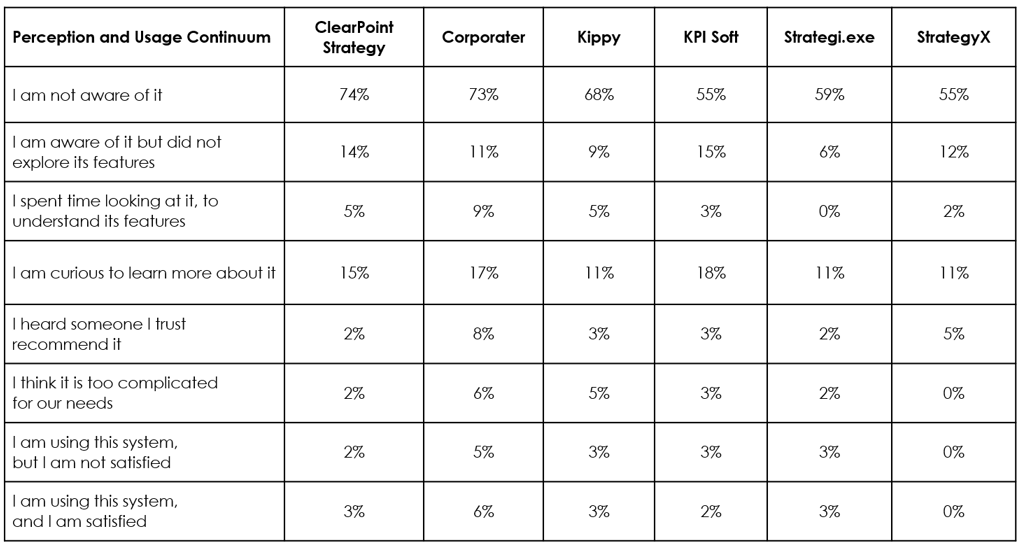

Table 4: System-specific perceptions and usage continuum